The anti-corruption agency SPAK has triggered a wave of investigations against top politicians in Albania. Deputy Prime Minister Belinda Balluku has been suspended from office and banned from leaving the country after being charged with irregularities in the awarding of the Llogara tunnel contract, among other things. A few months earlier, Tirana Mayor Erion Veliaj had already been arrested on suspicion of embezzling public funds.

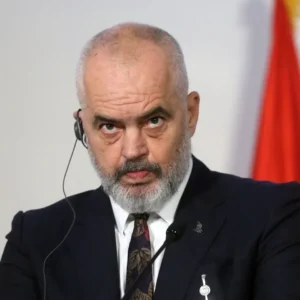

As the judiciary increasingly investigates the ruling party’s circle, political pressure is mounting on Prime Minister Edi Rama – in Tirana, in Brussels, and increasingly in Vienna as well.

Balluku, Veliaj & Co: Investigations in the inner circle of power

The Belinda Balluku case is considered the clearest sign yet of how far the investigations by the Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPAK) reach into the upper echelons of government. According to the indictment, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Infrastructure manipulated the tender for the billion-dollar Llogara Tunnel and effectively predetermined the winner – a massive violation of public procurement law and the principle of equal treatment.

A special court therefore suspended Balluku from office a few days ago. The politician rejects the allegations and speaks of “slander and half-truths,” but says she will cooperate with the judiciary.

Previously, the mayor of Tirana, Erion Veliaj, a close political ally of Rama, had been remanded in custody on corruption charges involving millions of euros. He is accused of diverting public funds to companies close to his family through bogus contracts.

Together with earlier cases—such as those against former ministers and members of parliament—this paints a picture of a ruling party whose top officials are increasingly in the crosshairs of the judiciary. Politically, this inevitably turns the spotlight on the man at the top: Edi Rama.

Scandal ambassador Velaj: Albania’s secret weapon in Vienna becomes a liability

Parallel to the investigations in Tirana, there has been controversy in Vienna for months over Albanian ambassador Fate (Fatmir) Velaj. Exxtra24, the investigative portal Fass ohne Boden, and several Albanian media outlets have documented a long list of allegations that go far beyond diplomatic improprieties.

The key points include:

- Possible secret service past: Former members of the Albanian services see Velaj’s unusually liberal travels before 1990 as evidence of contacts with secret services at home and abroad. Evidence in the legal sense has not yet been made public, but the question remains.

- Purchased titles & plagiarism: Velaj is said to have acquired academic degrees at the controversial “Krystal University” in Tirana. A plagiarism expert quoted by the media described his master’s thesis as almost entirely plagiarized.

- Social security and tax issues: According to reports, Velaj is said to have received social benefits in Austria at times despite his high income. At the same time, there are questions about income from book sales and art, even though diplomatic rules prohibit commercial activities. Whether and how this income was taxed has not been publicly clarified.

- Affair surrounding the “Toyota Yaris” case: According to Albanian and Austrian reports, Velaj is said to have temporarily granted protection in the embassy to a relative by marriage who is wanted in connection with a money laundering scandal.

For Rama, the ambassador has long been a political risk: in Austria, there are parliamentary inquiries and opposition demands to declare Velaj persona non grata. In Albania, on the other hand, the question arises as to why the head of government is sticking with a diplomat whose name keeps cropping up in new revelations.

“Rama wanted to intervene with Spiegel over article”

Media reports from Western Europe are adding to the pressure. In a detailed analysis, the German magazine Der Spiegel described Albania in 2024 as a country whose opponents accuse Rama of turning it into a “private narco-state.”

The article painted a picture of a state in which organized crime, drug trafficking, and politics are closely intertwined. At the same time, TV documentaries and research by other media outlets traced the role of Albanian groups in the international cocaine trade and raised questions about political responsibility.

In Tirana, there were reports of massive complaints against the reporting from the prime minister’s circle. This has not been officially confirmed – the government spokesman spoke in general terms of “one-sided and politicized portrayals.” But one thing is clear: Rama’s international image suffers the more often the country is mentioned in connection with corruption and drug trafficking.

Is EU accession jeopardized by corruption in Albania?

Rama’s strategic goal is clear: Albania should be a member of the European Union by 2030. Both the EU Commission and leading EU politicians regularly describe the country as a “frontrunner” in the enlargement process.

At the same time, the latest progress reports from the EU authorities attest to “some progress” in the fight against corruption, but still rate Albania’s preparedness as only low to moderate. The independence of law enforcement agencies, the systematic prosecution of money laundering, and protection against political influence are considered areas for improvement.

The establishment of the Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPAK) and the vetting process in the judicial system are expressly praised in Brussels. At the same time, the EU makes it clear that the quality of investigations and the political protection of institutions are crucial for further progress toward accession.

With each new arrest in the government’s circle, the risk grows that a “successful judicial reform” will become a political boomerang – especially if the impression arises that responsibility ends just below the level of the prime minister.

“SPAK must work faster and more independently”

Rama likes to present SPAK’s work as proof of his willingness to reform. Opposition politicians see things differently. Time and again, members of the Democratic Party and other critics say that the agency is too hesitant when investigations lead to the top echelons of government or Tirana City Hall.

Opposition politicians speak of a “selective approach”: while mayors, ministers, and ambassadors from Rama’s circle have remained in office for a long time, others have been dealt with more quickly. SPAK rejects such accusations and points to complex procedures, international legal assistance, and limited resources.

In fact, the special unit is confronted with a flood of cases – from municipal corruption scandals to million-dollar transactions abroad. The decisive factor will be whether investigators can visibly carry out their work at the highest levels without being politically thwarted. The handling of cases such as that of Ambassador Velaj will serve as a yardstick.

Edi Rama and his Milan connection

Parallel to domestic political pressure, Rama is focusing on the international stage and the diaspora. In addition to close relations with Italy – from controversial migration agreements with Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to billion-dollar energy and tourism projects – the prime minister is making targeted use of meetings with Albanians abroad in cities such as Milan to deliver political messages.

Rama has held several large events with the Albanian community in Milan, where he promoted investment in his homeland and coined the slogan “Albania 2030” – a promise to lead the country into the EU by the end of the decade.

Critics see this less as harmless diaspora populism and more as an attempt to cultivate an informal network of economic, political, and personal loyalties – far beyond Albania’s borders. There is no evidence of criminal activity in connection with these activities to date; but politically, the close interlocking of the state, the party, the economy, and foreign contacts reinforces the image of a system in which transparency often takes a back seat to loyalty.

Foreign Minister on charm offensive despite corruption scandal

Against this backdrop, Foreign Minister Beate Meinl-Reisinger’s (NEOS) recent trip to Tirana seems like a political counterpoint: On November 25, she met with Prime Minister Edi Rama and Foreign Minister Elisa Spiropali, praised Albania’s “extraordinary” progress in reforms, described EU accession by 2030 as “in Austria’s own best interests,” and once again highlighted the country as a “frontrunner” in the enlargement process.

She pointed to concrete steps such as Albania’s accession to the European payment system SEPA and emphasized that Europe would benefit “at least as much” from Albanian accession as Albania itself; at the same time, Spiropali spoke in her presence of “shared values” and an even closer Vienna-Tirana axis. So while in Albania the Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPAK) is investigating the innermost circle of power and EU reports continue to rate the country’s fight against corruption as only “certain” to “moderate,” there is no public mention of the fact that the Albanian ambassador in Vienna, of all people, has been under criticism for months due to numerous allegations and has become a domestic political risk for Rama.

The Austrian foreign minister’s almost euphoric upgrading of Albania – without visibly distancing herself from the open corruption scandals and without clear public conditions on transparency, SPAK independence, and the Velaj case – thus sends a mixed signal: While Brussels insists on a “track record” and resilience under the rule of law, Vienna seems to want to deliberately keep the political price for this EU course low.

Credits: APA

Recent Comments